William Arabin, the most eccentric judge in the history of English and Welsh law

As we have seen in previous letters, there are some judges who go down in history with a capital letter for their great contributions to the law of England and Wales. Names that, thanks to their great knowledge and decisions, will mark the destiny of their people, are forever engraved in gold letters in marble.

They are exceptional people with extraordinary intellectual qualities, extraordinary brains for the future of an entire country. There are titans of the stature of Lord Denning, Lord Wilberforce or more recently Lady Hale or Lord Sumption, among other exceptional figures in British law.

And then there are other judges who have also gone down in posterity, but not for their marvellous and enlightened minds, but quite the opposite: for being absolutely eccentric and bizarre in the exercise of the judiciary, for their constant outbursts and a logic closer to the most absolute of Berlinian absurdities than to the straight dictates of the law.

This is precisely the case of ‘Serjeant Arabin’.

ARABINIANA’, A BOOK FOR THE GLORY OF THE MOST OUTLANDISH JUDGE

As the story goes, in 1843 a small book of only sixteen pages appeared in London under the title “Arabiniana”.

Its author cautiously concealed himself under the enigmatic initials “H.B.C.”, and no other details leading to his identification were known.

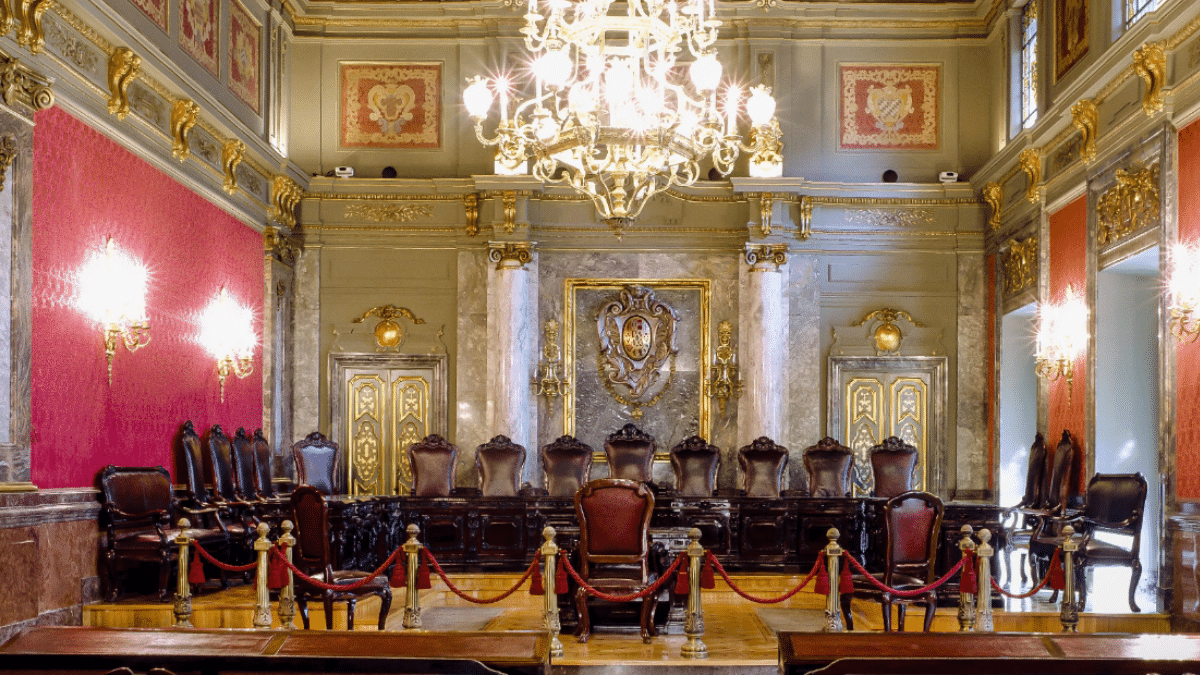

This little book contained some of the more remarkable witticisms of Judge William St Julien Arabin, who practised from the mid-19th century at London’s most famous criminal court, the Central Criminal Court, better known as the Old Bailey.

Arabin was one of the last of the Serjeant-at-Law, or as they were then known: the Serjeants; an ancient order of barristers with several centuries behind them, whose origins date back to no less than 1300 and which, according to some historians, was the oldest in England.

In fact, for centuries the ‘Serjeants’ held exclusive jurisdiction over the so-called ‘Court of Common Pleas’, being the only lawyers who had the right to defend a case before this court or in other courts such as the ‘Court of King’s Bench’ or the ‘Exchequer of Pleas’, all of which have now disappeared.

This order emerged as a true elite of barristers, forerunners of the current King’s Counsels, who took on a large part of the work in the central courts of English jurisdiction, given that only the Serjeants-at-Law could be judges in these courts until the 19th century, being socially above other orders in the country.

This is precisely the origin of the English tradition that only some of the most prestigious barristers were allowed to enter the judiciary, since here practice in the forum has always been more valued than having all the theory in one’s head.

In short, this ‘Serjeant Arabin’ was a judge of the old common law but very particular in his interventions, which is why H.B.C. dedicated this little book to him, collecting the absurdities of this old judge, thus achieving his place for posterity.

NOTES FROM THE COURT HEARINGS BEFORE AND AFTER LUNCH

As we have explained on previous occasions, the sentences that resolved the cases brought before His Gracious Majesty’s courts were not published more or less systematically as they are today.

On the contrary, the reasons that led British judges to rule one way or another were recorded in simple notes drawn up by young barristers sitting on the back benches of the courtrooms.

They would then pass these notes on to pretty paper and share them with their chambers colleagues in order to keep abreast of new developments in the law, as certain aspects of the judgments became the law of England and Wales, as we know.

This gave rise to the famous ‘Law Reports’.

It is precisely in this tradition that ‘Arabiana’ is framed, given that H.B.C. compiled the astracanadas of the ‘Serjeant Arabin’ while this judge was presiding over the famous criminal court and collected by the ‘barrister’, undoubtedly holding back his laughter.

As a curiosity, each case is identified in the book with the names of the parties but also including the initials ‘A.P.’ and ‘P.P.’, referring to the Latin expression ‘Ante Prandium’ and ‘Post Prandium’.

In other words, the hearing was held either before or after lunch, given that hearings are held here in the morning as well as in the afternoon.

However, as confirmed by several authors, it has not been possible to detect any substantial difference in the decisions taken by Arabin attributable to the food or any other element derived from this judge’s agape.

In other words, Arabin was the same horror before and after eating.

Indeed, thanks to this judge’s wit and humorous outlets, ‘Arabiana’ was reprinted several times, even outside the United Kingdom, such as the edition published in Philadelphia in 1846, leading to thousands and thousands of readers throughout the English-speaking world, a legion of true ‘Serjeant Arabin’ fanatics.

In fact, the great British judge Sir Robert E. Megarry took it upon himself in 1969 to prepare his own critical edition under the name of ‘Arabinesque-at-law’, correcting many of the inaccuracies and errors of the first edition of the ‘Arabiana’.

A JUDGE WHO LEFT AN INDELIBLE MARK ON ENGLISH LAW

According to the most benevolent descriptions of the time, ‘Judge Arabin’ was a “peculiar man, with an absent-minded and eccentric air, not lacking in innate wit, but lacking in the faculty of rational expression”.

These words belong to the obituary dedicated to him in ‘The Times’ by one of the leading authorities on English law, Sir Frederick Pollock, author of the monumental “History of the Law of England before the Time of Edward I”, among many other essential works on English law at the beginning of the 20th century.

Moreover, fellow ‘Serjean’ William Ballantine said of Arabin that he was “a cunning and picturesque little man”, who “uttered absurdities with the most perfect innocence”.

You get the drift.

No wonder, then, that another judge, this time ‘Serjeant Robinson’, agreed in saying of Arabin that he was “a thin, old, wise-faced man, very eccentric in his ideas and expressions, and even more so in his logic”.

In addition, Judge Robinson clarifies some of the possible reasons for Arabin’s particular way of being as he was “very short-sighted, and also very deaf”.

Thus, Robinson explains that Arabin’s notes from the trials he presided over “were almost indecipherable to anyone, even to himself. The letters were deformed enough as it was, but his numbers were much worse”.

So, thanks to this little book we have preserved like insects trapped in amber Arabin’s outbursts during the fourteen years he was at the Old Bailey to the amazement of barristers, solicitors and above all the poor defendants who had to face the flamboyant judge.

I leave you with the first pearl.

On one occasion, during a trial, a barrister once complained about the excessive ventilation in the courtroom.

And the ‘Serjeant Arabin’ replied:

– ‘Yes. When I sit here, I imagine that I am on the top of the mountain; and the first thing I do every session in the morning is to go to the mirror and check if my eyes have not already flown out of my head.’