Some are eco-sustainable and others build more power plants. Some make bikes and others make money. Decarbonisation is a business not only for the Chinese and Americans, but also for savvy Europeans.

The British are paying dearly for the policies of recent years to replace coal, oil and natural gas with wind turbines and solar panels – policies, incidentally, pursued by the Conservatives. Last year the UK spent £3.5 billion (more than 4 billion euros) buying energy from abroad.

Windmills and solar panels do not meet the demand of the coal and nuclear power stations that have been closed in recent years. The UK authorities have therefore relied on energy imports from France, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark via undersea cables.

According to a report by the London Stock Exchange Power Research, based on official data, electricity sales by France between January and November 2023 cost the UK £1.5 billion (more than 1.7 billion euros). The Norwegians were paid about 500 million pounds.

Britain’s growing dependence on foreign energy supplies explains why Rishi Sunak’s government announced last July the granting of 100 new licences for the search and extraction of oil and natural gas in the North Sea, although the prime minister added that his goal remains complete decarbonisation by 2050.

True to the climate religion, several Conservative and also Labour MPs have opposed these new licences. The French are rubbing their hands together, as the headline in The Telegraph, which published the above-mentioned report, says.

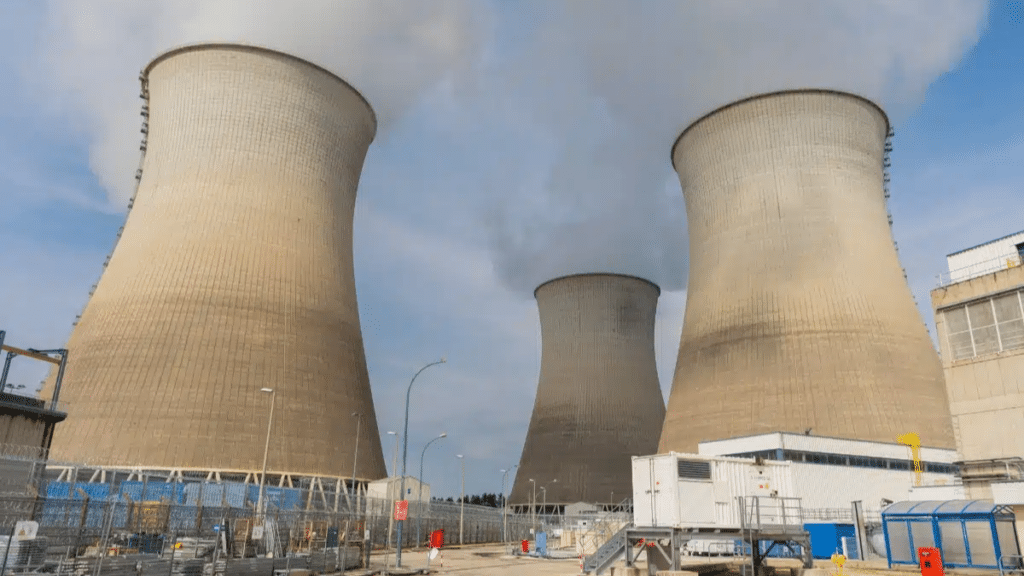

While the dozens of French nuclear reactors provide energy for industries and citizens and bring in billions of euros in revenue, in Spain, on the other hand, the “progressive” government has announced a plan to irreversibly close the few remaining plants, spending more than 26 billion euros.

The stubbornness of vice-president Teresa Ribera and her boss, Pedro Sánchez, against nuclear energy in Spain is surprising, although they follow the policy of the PSOE, as Felipe González stopped the plan to build power plants designed during the Franco regime. In the EU, on the other hand, the recently ended Spanish presidency has allowed the expansion of nuclear power plants in the rest of Europe.

Why this difference in treatment of the same energy; why nuclear is good in France or Finland and bad in Spain; on what science are Sánchez and Ribera basing this discrimination; or is it not science that drives their actions, but something tangible?